Global Adaptation Indicators And Pakistan’s Struggle To Turn Climate Ambition Into Action

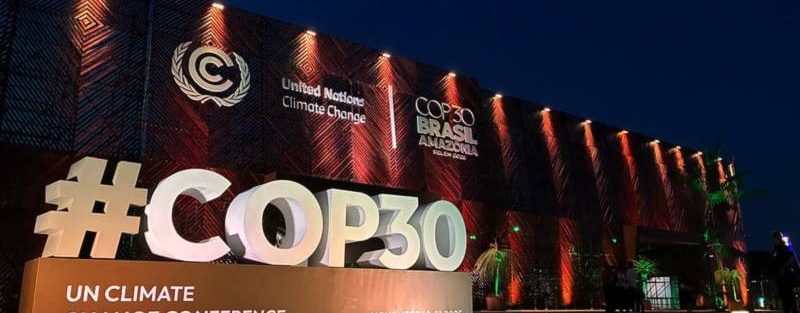

Global adaptation indicators advanced at the Belém summit, but weak finance and domestic systems risk leaving Pakistan’s climate plans symbolic

Climate adaptation is a linchpin of global climate action, an essential complement to mitigation in meeting the Paris Agreement’s objectives of limiting global temperature rise and strengthening resilience to climate impacts. While mitigation slows down the pace of climate change through emissions reduction, adaptation enables communities to prepare for and withstand current impacts.

Article 2 sets a temperature limit of 1.5°C, achievable through mitigation and decarbonisation, and Article 7 underscores enhancing adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience, and reducing vulnerability, establishing the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA). It recognises adaptation as a global challenge to be addressed at multiple scales and encourages countries to develop and update their National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) and adaptation communications.

Although the intent behind establishing the GGA was to create a shared framework for tracking progress, identifying gaps, and mobilising resources for adaptation, it did not adequately reflect what progress would look like or incorporate assessment metrics. It was not until 2021 at COP26 that the real technical work on adaptation under the Glasgow-Sharm el-Sheikh work programme began, and a framework surfaced at COP27. At COP28, the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience was agreed upon, adapting a global priority. It included provisions on developing relevant indicators for measuring adaptation targets of the GGA under the United Arab Emirates–Belém work programme.

Despite this achievement, the absence of indicators constrained GGA’s progress. Selecting pertinent indicators proved to be complex due to the cross-sectoral and context-specific nature of adaptation. Experts struggled to narrow down thousands of potential indicators to a manageable set of fewer than a hundred that balanced technical robustness with political and practical feasibility.

After two years, COP30 negotiators in Belém finalised a consolidated list of 59 indicators, the Belém Adaptation Indicators, for tracking adaptation progress across key adaptation sectors and means of implementation (that is, finance flows, technology transfer, and capacity-building). A two-year Belém–Addis vision is tasked with developing guidance for operationalising the indicators so countries can align their adaptation policies with global ambition.

An important lesson emerging from the COP30 process is that translating global ambition into national action does not rely solely on indicators, but also on whether countries have adequate systems, resources, and support in place to integrate these metrics into their existing planning tools.

The NAP is a step forward; however, without stronger foundations, it risks remaining symbolic rather than transformative

For countries like Pakistan, where adaptation is not an abstract global agenda but a matter of survival, alignment of GGA indicators with its National Adaptation Plan (NAP) translates into robust national systems and context-specific planning. Effective adaptation implementation and meaningful progress on global indicators rely on assessments rooted in domestic realities, local data, and planning that reflects the full scale of country-specific hazards.

The catastrophic floods of 2022, which affected 33 million people and caused damages exceeding $30 billion, underscored the country’s acute vulnerability and prompted the development of its first-ever National Adaptation Plan (NAP 2023–2030), making it one of the 67 developing countries to submit such a plan. The document outlined a roadmap for resilience across six priority areas, emphasised adaptation mainstreaming in its rationale, and envisioned a climate-resilient country. Its formulation process involved consultations with government bodies at both national and provincial levels.

However, it fell short in capturing local realities by excluding civil society, academia, and indigenous communities, weakening ownership and the integration of traditional knowledge, which are critical to responsive adaptation strategies. Furthermore, its scientific evidence draws largely from external datasets rather than local sources, which are vital for understanding how impacts may manifest in the future and for implementing targeted, evidence-based actions.

While the NAP enlists investment sources primarily foreign funding, and outlines financial needs, it lacks evidence on how these needs were derived and how incoming finance would be operationalised. The absence of a strong finance-needs narrative grounded in local realities and a future development vision stalls alignment between national adaptation planning and the GGA.

Pakistan needs the means of implementation and therefore requires a robust finance narrative, like other developing and vulnerable countries. There was a push by least-developed countries (LDCs), supported by the African Group, Small Island Developing States (SIDS), and some Latin American countries, to triple grant-based adaptation finance by 2030 compared to 2022 levels. The Glasgow Climate Pact’s goal of doubling international public adaptation finance from the 2019 baseline to around US$40 billion by 2025 also expired this year.

Despite the COP30 presidency’s “global mutirão” reaffirming expectations on doubling finance and efforts towards tripling, the final text did not mention the 2025 baseline and pushed the deadline to 2035. The nature of tripling finance also remains vague. While the adoption of indicators was a breakthrough, COP30 failed to meet the expectations of developing countries for a new adaptation finance target. This jeopardises global adaptation scaling efforts, given the current adaptation finance gap.

Global financial uncertainty, overreliance on external funding, and weak domestic systems governance, data, and participation limit Pakistan’s adaptation progress and alignment with GGA indicators. The NAP is a step forward; however, without stronger foundations, it risks remaining symbolic rather than transformative.